6 ‘Best practices’ in supervisory and non-executive boards

When we as Strategic Management Centre (SMC) facilitate self-evaluations of supervisory boards (SBs) or one-tier boards (OTBs) with non-executive directors, we notice recommendable pracitices as well as ones that could do with improvements. In our own supervisory boards we experience good and less good practices. As our investment in the board membership profession and to the benefit of our clientele, we have summarised and analysed the best pratices, that we have encountered. These apply to two-tier boards that have a supervisory board as well as to one-tier boards with non-executive directors. Both are called ‘boards’ in this article.

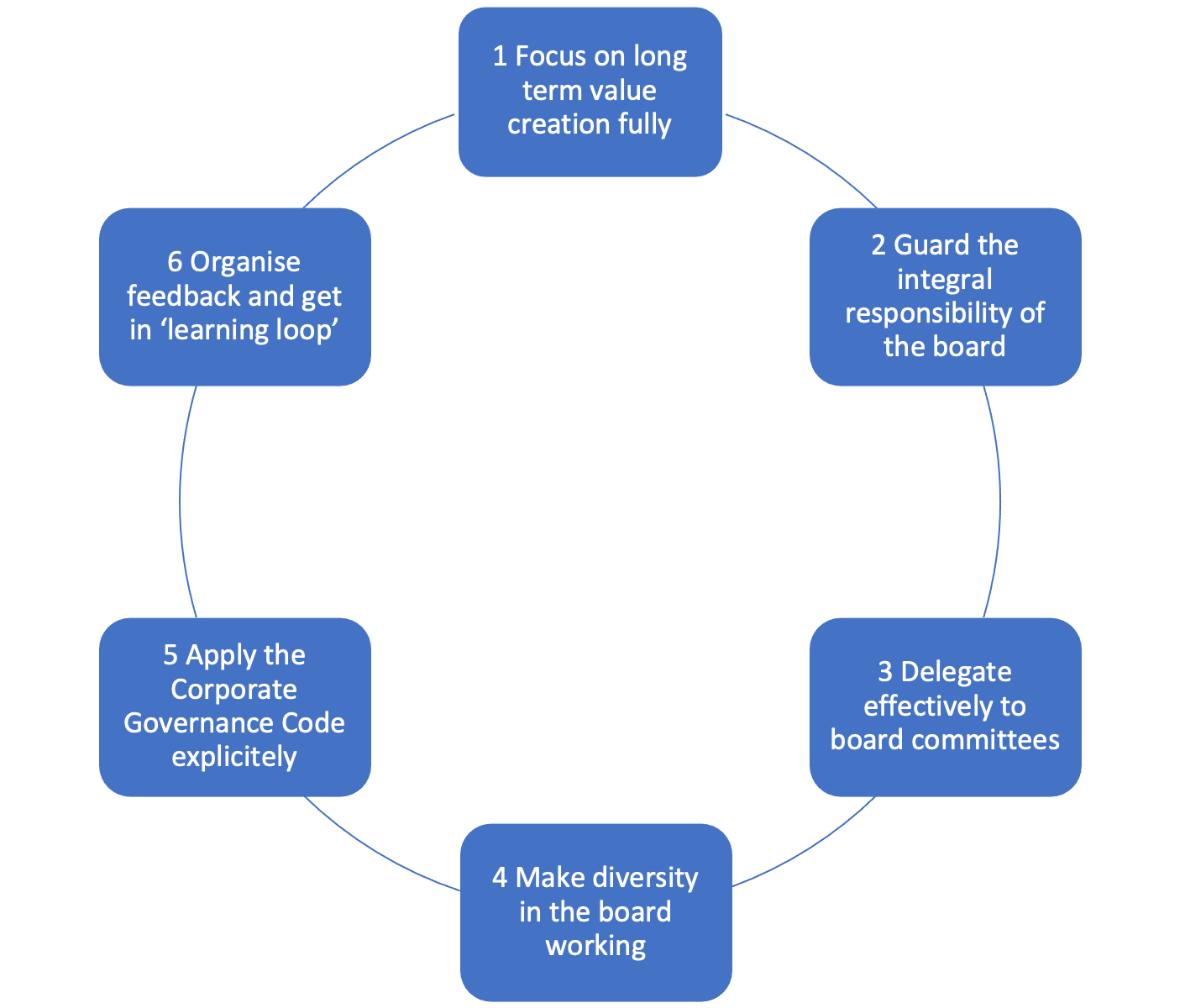

Six related subjects appear to be of importance for proper fulfilling the roles of boards. These are:

In this article we provide a brief overview of recommendable practices, if applicable linked to suboptimal ways of working. In further articles we will expand on each of these recommendable practices.

- Focus on long term value creation fully

Everyone would agree that one of the most important roles of the board is to ensure, that management creates long-term value (LTV). LTV regards creation of value for all stakeholders, meaning shareholders, employees, customers, neighbours and other societally involved. LTV goes beyond business strategy. Important is the role in society, ‘the purpose’. Thereby is contributing to sustainability, an important component of LTV. Further, part of LTV is aligning with societal and business dynamics such as digitalisation, essential given the long term aspects. LTV should be a core element of the strategy, the one the management board executes and non-execitives supervise.

Athough few would disagree, we hear frequently at self-evaluations, that the short term subjects are predominant, as there are urgent matters to speak about and these end up taking a lot of time. Also the importance of ‘being in control’ results in many reports, and extensive reading and speaking time.

Spending sufficient attention to LTV demands a pro-active stance. This starts with the executive team, that itself should aim for LTV and report comprehensively to the supervisory board. Further it is up to the board to allocate sufficient time and attention wider than for ‘here and now’, the longer term. This can be achieved through clear protocols, like periodically acting as sounding board, placing LTV on the agenda and allocating time to discuss. This can also be done based on management dilemmas, in off-site meetings and visits to parts of the organisation that the board supervises.

- Guard the integral responsibility of the board.

Pivotal in the governance of boards is the interaction between the charman of the board and the CEO. Good interaction and strong professional relarionship between these two apear in many organisations to be the engine of success, that leads to good performance and adequate problem solutions. Transparant information, strong mutual trust and execution power appear to be decisive for good performance.

The other non-executive board members could be excluded as they, only at a later stage, get the opportunity to be informed and to discuss what the chairman and the CEO have already decided and done. Consequently many supervisory board members feel too distanced from the decision making and that integrate supervisory board decision making is not done justice. They may even pose that they are confronted with ‘a fait accompli’.

There appear to be several good ways of working. The chairman who is aware of his mandate and considers himself as ‘directing the play’ towards his fellow board members and informs and consults them, avoids getting to far ahead of the troops.

Sharing (management) dilemmas instead of conclusion loaded introductions leads to more participation. Shortage of time appears practically a bottleneck. We see effectively cooperating boards communicate on the fly by using (video) conference calls and whatsapp groups.

Communication by a non-execitive board member beyond board meetings with others than the CEO, like shareholders, employee representatives, customers and others affected by the organisation, is essential for good functioning. In a number of organisations this is acknowleged, and often, initiated by the CEO or chairman, there are structured meetings with these stakeholders. The role of the non-executive in these contacts should be more a listening one than a messaging.

In SMC research ‘Poldering on a World Stage[1] regarding the supervisory boards of intermediate holdings – i.e. Dutch ‘structure corporations’, that are part of an interational group – it appears that non-execitive directors have large responsibility herein and that they have an obligation to search the information and contacts. In the ‘struggle between formality and substance’ it appears that supervisory board have a greater impact if they have a proactive attitude and gather information from various sources.

- 3. Delegate effectively to board committees

Many supervisory boards and boards of directors work with committees such as the Audit & Risk Committee and/or the Nomination & Remuneration Committee. This is necessary in order to divide the supervisory boards work and to gain more depth, expertise and interaction between the board and management, as well as not to burden the integral supervisory board too heavily. Sometimes a supervisor such as the AFM (The Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets) or DNB (De Nederlandsche Bank) insists on this. While this is good practice, it can go too far. In our practice, we come across that audit & risk committees regard almost all subjects as a risk and therefore fall within their competence. Consequently, decisions are made in the audit & risk committee about investments, which also have major consequences for strategy implementation, employment and sustainability, which are really subjects that concern the whole supervisory board.

In many self-evaluations, supervisory directors and the board express that they are not involved in idea generation and decision making on certain subjects. They leave these subjects to the committee members, because they do not have the knowledge and information. There are supervisory directors who complain that they are responsible for certain decisions, but are not sufficiently informed about these.

When it comes to ‘’best practices’’, we experience a combination of principles and pragmatics. The basic principle is that decisions can only be taken within the integral supervisory board. The specific committees prepare these decisions and make proposals. If supervisory directors have a lack of information or knowledge, they are additionally briefed to enable them to participate equally in the decision-making process.

A specific, but not unimportant, aspect is the choice whether or not the supervisory boards chairman can also be chairman or member of a committee. In general, combining an integral supervisory board chair with a committee chair can not be seen as ‘’best practice’’. Based on experiences with various supervisory boards, we also would not recommend committee membership by the supervisory boards chairman in order to give the committee and its chairman sufficient space.

- Make diversity in the board working

The importance of diversity, achieving robust dialogue and avoiding tunnel vision are widely recognised. Many supervisory boards are actively working on a diverse composition: more women, more people with a migration or international background, different work experience and networks, younger members, et cetera. These boards are increasingly successful at this. This year, for example, more women than men were appointed within the supervisory board of listed companies in The Netherlands. A point of attention, in our experiences, is to let these various members come fully into their strength.

Although there is a conscious effort to achieve diversity, it appears to be more difficult to understand each other within supervisory boards with a more diverse composition. This is caused by both the sender and the receiver having different values, habits and expectations about what should be said with what immediacy at which level of abstraction. If the ‘old management culture’ is dominant, the image of ‘the new ones do not understand’ quickly arises. With stacked diversity characteristics it becomes even more complex.

‘Making diversity work’ is essentially about equality and respect. There is a role for the chairman, and certainly for all other supervisory board members. This requires an open, welcoming attitude, even as far as ‘you are right, even if you are not’. In addition, good support in introductory phase, pre-discussion of meetings and a ‘buddy system’ appear to have good effects.

- Apply the Corporate Governance Code explicitely

The Corporate Governance Code (CGC) applies to listed companies and has been developed and expanded over the past decade originating from the stakeholders and is enshrined in law. A number of industries, such as housing associations and healthcare institutions, use a Code derived from the CGC. Many non-listed companies are aware of the code and tend to apply it.

In self-evaluations, the code appears to be relevant if differences of opinion about governance issues emerge. Often the roles and responsibilities are not fulfilled or combined in a pure way: ‘a corner is cut’ somewhere’. In these cases, the code appears to provide guidance and lead to best practice solutions – accepted by all. We do know companies that have made explicit to what extent the CGC applies to them, and where this is not the case, how they have set up their governance. They constantly use this yardstick to calibrate their governance.

- Organise feedback and get in ‘learning loop’

Many experienced supervisory directors consider themselves ‘experienced practitioners’. Building on experiences elsewhere, they fulfill their role within the supervisory board. They do this with limited support in a limited number of sessions per year. In addition, they are part of a team of which they often do not know the other team members well and who are also constantly ‘refreshed’. This can lead to an overly isolated attitude.

We notice that it is important to properly organise feedback on individual and collective performance. For supervisory board members it helps both individually and collectively to take the attitude of ‘no one is beyond feedback’. In this way you can give each other feedback during self-evaluations, and even continuously, and optimise your contribution. Working on good teamwork in the supervisory board also requires that this interaction and the role of everyone can be discussed. In self-evaluations, this is often one of the most challenging topics that gives the highest yield. There are various ways in which this can be organised in an effective and efficient way, without falling into a ‘courtesy round with tops and tips’.

The self-evaluations show that the functioning of a supervisory board and its members, in terms of information processing, cooperation and decision-making, is a unique process that certainly does not run optimally. However, it appears that many supervisory boards have to deal with the same issues and can learn from each other what ‘recommendable practices’ are. We have summarised our experiences in this article. Hereafter, we will further develop these experiences and insights for each ‘recommendable practice’.

* I would like to sincerely thank Ludwig Hoeksema, Geert de Jong, Anita Lettink, Jaap van Manen, Jan Maarten van der Meulen, Arno Pouw, Albert Jan Stam and Jaap Westenburg for their contributions.

[1] ‘Poldering on a World Stage’, a study of supervisory directors of intermediate holding companies struggling between formality and substance (by dr. Ludwig Hoeksema, prof. Geert R.A. de Jong and Jaap Westenburg LL.M.)